Black Ribbon for Mourning was created in 2017 by Dr. Kim Brillante Knight with collaborators Dr. Jessica C. Murphy and Dale MacDonald. The project was conceived for the HASTAC 2017 exhibition on the Wearable and Tangible Possible Worlds of Digital Humanities (DH), an exhibition that collectively suggested that one of the possible worlds of DH is material, embodied, and grounded in feminist approaches that are attentive to issues of gender, race, class, ability, sexuality, class and their intersections.

Introduction

The project starts with a number: 309.

According to MappingPoliceViolence.org, there were 309 Black people killed by the police in 2016. While Black Americans made up only 13% of the U.S. population in 2016, they accounted for 26.7% of people killed by the police that year. Black Ribbon for Mourning draws connections between the contemporary epidemic of police killings that grows out of anti-black racism and the logics and economy of the 17th-century slave trade.

In Molly Farrell’s Counting Bodies, one of the texts by which Farrell explores early practices of human accounting is Robert Ligon’s book, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados. Among the notable qualities of Ligon’s 1657 text, Farrell suggests, is that Ligon’s clothing budget for the sugar plantation articulates social hierarchies and is performative in the way that it conflates people and commodities. Ligon writes, “Black Ribbon for mourning, is much worn there, by reason their mortality is greater, and therefore upon that commodity I would bestow twenty pound” (qtd. in Farrell 95).

Ligon’s casual enumeration of the hidden costs of 17th century mortality of enslaved persons and the attendant costs of mourning rituals reminds us that data points and their articulation often suppress the complexity of lived realities. The two instances, separated by 359 years, are connected in many ways, including that they share a logic of misplaced solutionism. For Ligon, the solution to mortality of enslaved persons is not to abolish the conditions of slavery, but to budget more money for the signifiers of mourning. In contemporary policing, solutions are often sought in militarization or surveillance technology, rather than examining the fundamental principles of policing itself.

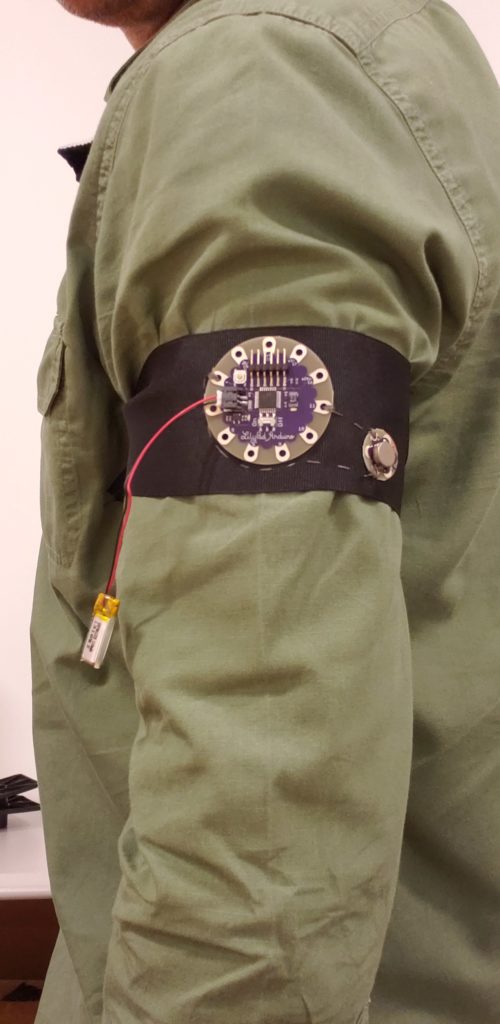

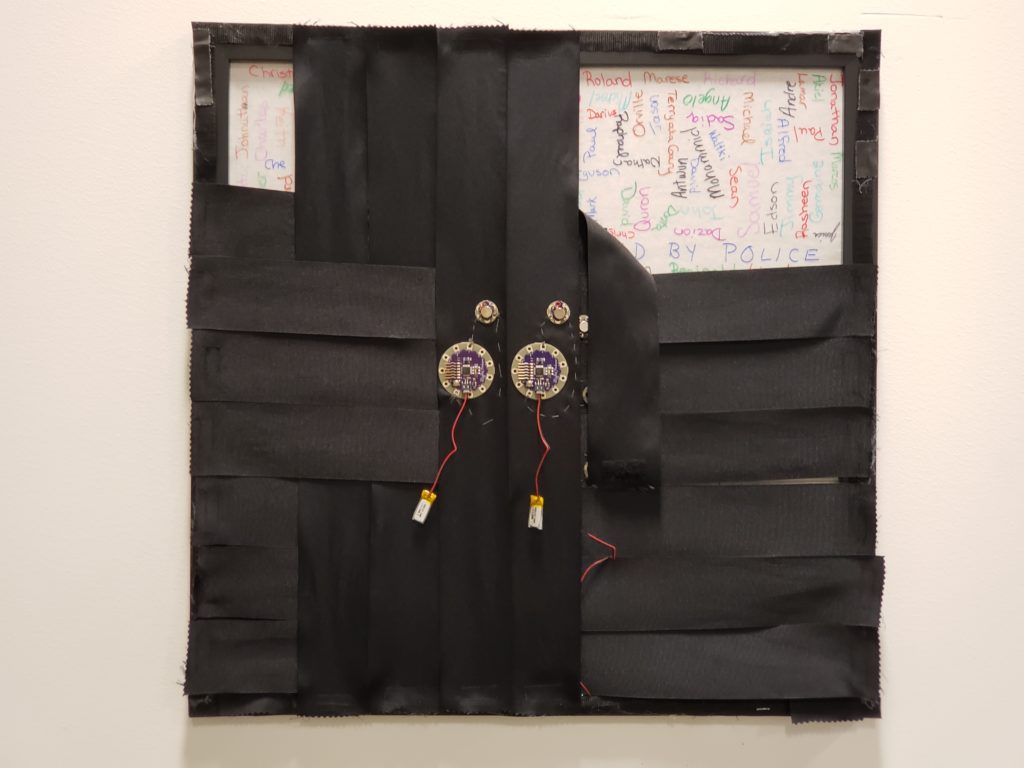

Black Ribbon for Mourning involves a square frame mounted on a wall. 20 black ribbons, in reference to Ligon’s twenty pound, are woven together. As participants approach the square, they are invited to remove a ribbon and tie it around their arm.

Originally conceived for a four-hour exhibition, the entire “year” passes in four hours, with each day lasting 39.3 seconds. The ribbons have a vibrating motor sewn into them and are programmed to pulse, with each one-second vibration representing a black person killed by police in 2016. A longer vibration indicates multiple people killed in one incident, while multiple short pulses signify separate incidents. Carrying the ribbon with them, the wearer experiences a faint vibration, timed at intervals that do not, cannot, make sense.

As ribbons are removed from the tapestry, the first names of those killed become visible, gesturing towards the possible world where black lives are named and matter, which can only happen in the absence of black ribbon.

Black Ribbon and Memorializing

The code Knight created for the project became a ritual in memorializing. Instead of a calculated loop, it is a hand-coded list where any time there is code to trigger a vibration, there are notes to include the name of each person killed. In some cases the notes include details about the person’s death, such as the January 10th death of Gynnya McMillen who was only 16 years old and died as a result of restraint when taken into custody at a juvenile detention center in Elizabethtown, KY. By engaging directly with the data, the details of police violence unfold. For instance, though firearm deaths tend to garner more attention, there are a number of car crashes, falls, and other causes of death. This suggests that police violence stems from multiple strategies of policing, transcending safe firearms or de-escalation training. The process of writing the code brought Knight close to the data, as she sat with it for hours, alternating between reading accounts of the deaths and calculating instructions for the Arduino.

http://github.com/purplekimchi/blackribbon

Murphy hand wrote each name on the glass of the frame as her daughter read the names aloud as part of her ritual of memorializing. In both cases, this was an attempt to recognize the lives behind the data. The handwriting is imperfect. The code is not elegant. In fact, it is somewhat glitchy. But how could it not be? The texture of the data, to cite Bowker and Starr, lives in the acts of naming and in allowing the imperfections to stand as we refuse the imperative to efficiency.

The project asks users to be with this data for up to four hours, allowing the archive of names encoded in the armband to operate upon them.

This project is not an attempt at technologically manufacturing empathy. It is a work that explores non-visual witnessing over the course of several hours while participants wear data-engaged haptics. This allows data to be accessed by the body without reliance on visuals. The context in which the frame is installed lends a site-specific meaning, but the body on which the armband is worn extends the notion of site-specific installation, inserting the project into whatever other activities the wearer might be engaged in during the installation. For some it may be a reminder; for others a prompt to reflect on complicity; for still others, a process of witnessing.

Technical Specifications and Production

Black Ribbon for Mourning was created by collaborators Kim Brillante Knight and Jessica C. Murphy, with technical consultations with Dale MacDonald.

The project uses Arduino, an open-source platform, which includes hardware, a coding language, and interactive development environment. The full code of Black Ribbon for Mourning can be viewed at http://github.com/purplekimchi/blackribbon

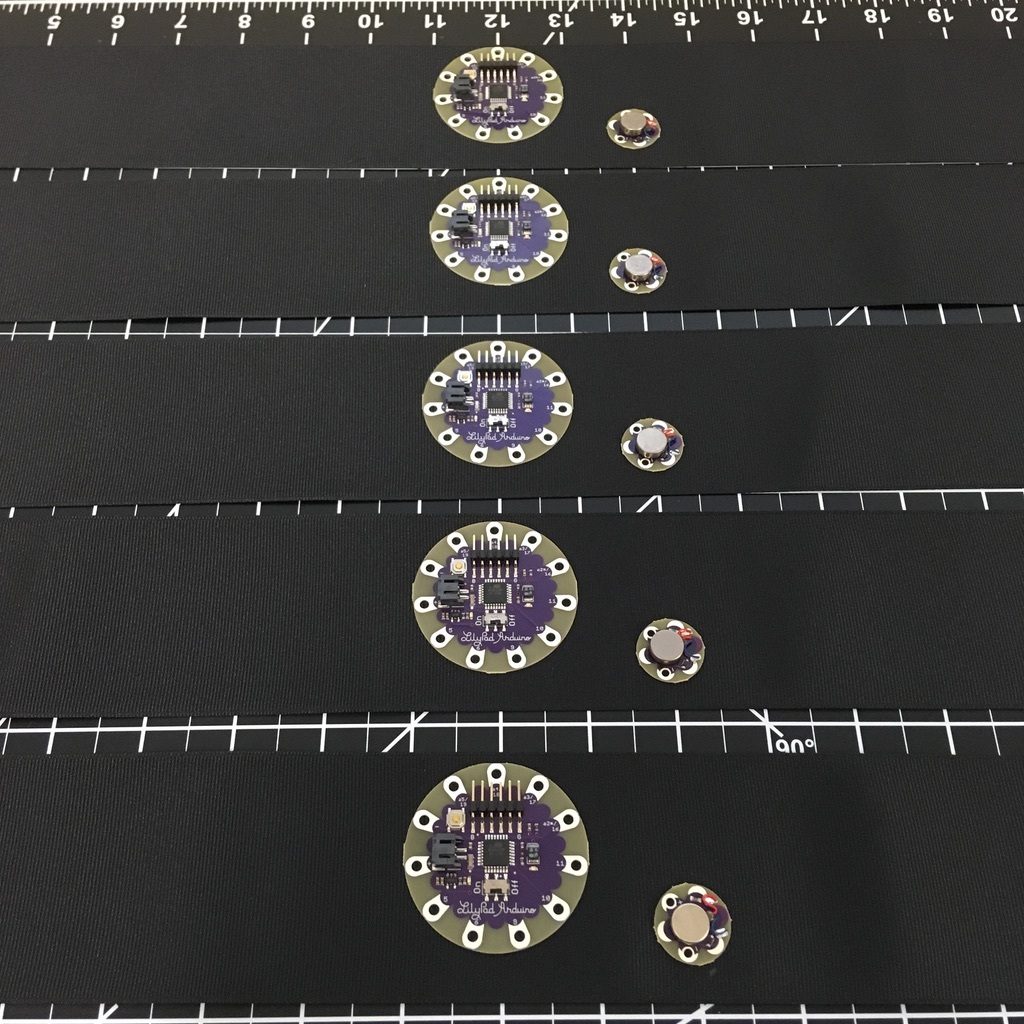

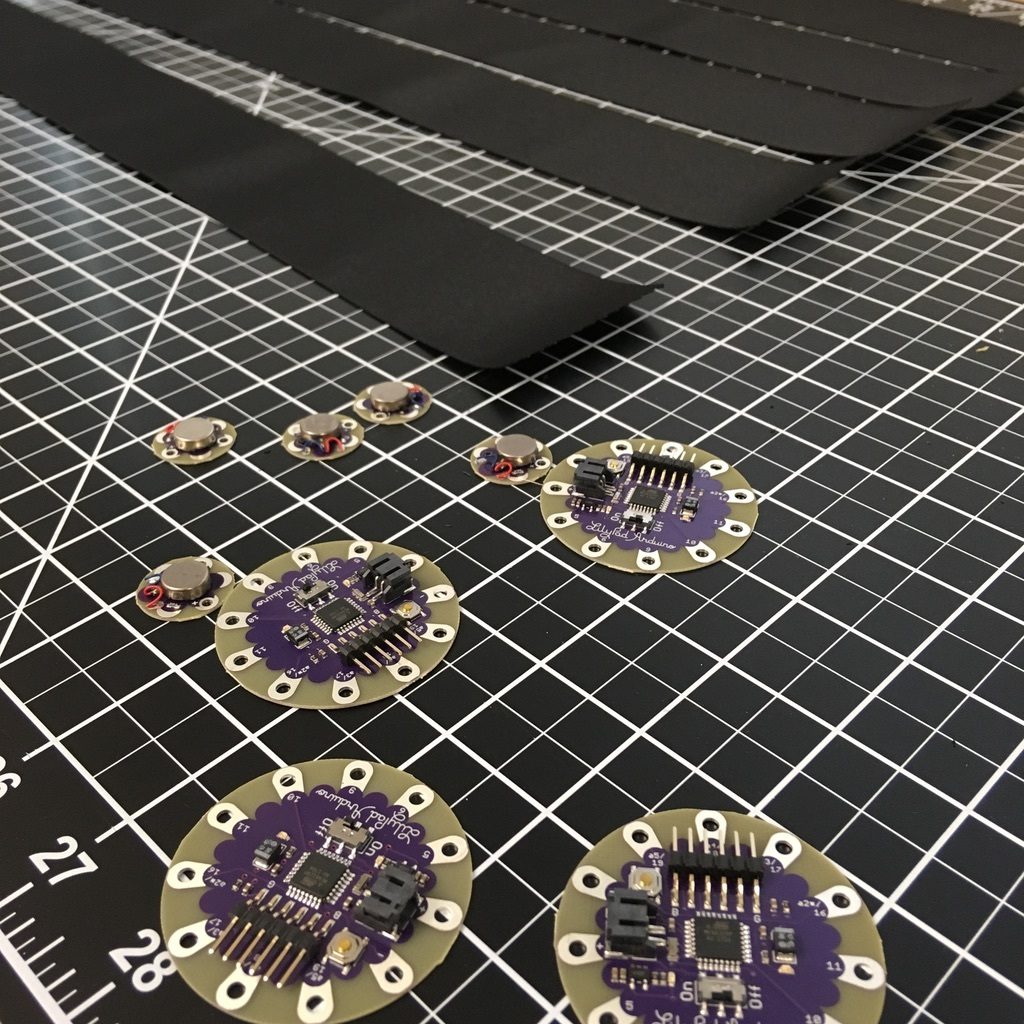

The project includes twenty 2-inch wide black grosgrain ribbons, onto which is sewn a LilyPad, a type of Arduino microcontroller. The LilyPad Arduino was invented by Leah Buechley, formerly of MIT’s High-Low Computing group. Buechley created the LilyPad to introduce engineering into different contexts, as evidenced by the large round connections, through which a needle and conductive thread can pass. A vibrating motor and rechargeable LiPo e-textiles battery are also sewn into each ribbon.

The project was supported by UT Dallas’ Feminist MakerSpace “Stitch n’ Bitch” event in which stitching support was provided by Elwyn Crawford, Letícia Ferreira de Souza, Morgan Grasham, Juan Llamas-Rodriguez, Josef Nguyen, and Hong-An Wu.

Citations:

Bowker, Geoffrey and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. MIT Press, 2000.

Farrell, Molly. Counting Bodies: Population in Colonial American Writing. Oxford UP, 2016.